A New York nurse working in ICU has posted a harrowing story of her heartbreak as she accompanies a patient to the point of death. We have become inured to the videos and stories from Italy and we no longer comprehend the stats from the medical officials dashboards. This one story makes it all unbearably real. This is a story of the Crucifixion. Her name is Jennifer. This is her story.

====

I lost a patient today. He was not the first, and unfortunately he’s definitely not the last. But he was different. I’ve been an ER nurse my entire career, but in New York I find myself in the ICU. At this point there’s not really anywhere in the hospital that isn’t ICU, all covid 19 positive. They are desperate for nurses who can titrate critical medication drips and troubleshoot ventiltors.

I’ve taken care of this man the last three nights, a first for me. In the ER I rarely keep patients for even one 12 hour shift. His entire two week stay had been rough for him, but last night was the worst. I spent the first six hours of my shift not really leaving his room. By the end, with so many medications infusing at their maximum, I was begging the doctor to call his family and let them know. “He’s not going to make it”, I said. The poor doctors are so busy running from code to code, being pulled by emergent patients every minute. All I could think of was the voice of my mom in my head, crying as I got on the plane to leave for this place: “Those people are alone, you take good care of them”. I was the only person in that room for three nights in a row, fighting as hard as I could to keep this man alive. The doctor was able to reach the family, update them. It was decided that when his heart inevitably stopped we wouldn’t try to restart it. There just wasn’t anything else left to do.

Eventually, he gave up. It was just him and me and his intubated roommate in the next bed. The wooden door to the room is shut, containing infection and cutting us off from the rest of the world. I called the doctor to come and mark the time of death. I wished so much that I could let his family know that while they might not have been with him, I was.

I shut the pumps down (so horribly many of them), disconnected the vent, took him off the monitor. We didn’t extubate him, too much of a risk to staff. Respiratory took the vent as soon as I called. It’s just a portable one, but it’s life to someone downstairs. The CNA helped me to wash him and place him in a body bag, a luxury afforded only to those who make it out of the ER. Down there the bodies pile up on stretchers, alone, while the patients on vents wait for the golden spot my gentleman just vacated. We’ll talk about the ER another time. My patient was obviously healthy in his life. I look at his picture in his chart, the kind they take from a camera over a computer when you aren’t really prepared. A head shot, slightly awkward. I see someone’s Grandpa, someone’s Dad, someones Husband. They aren’t here with him. My heart breaks for them.

I fold his cute old man sweater and place it in a bag with his loafers, his belongings. I ask where to put this things. A coworker opens the door to a locked room; labeled bags are piled to the ceiling. My heart drops. It’s all belongings of deceased parents, waiting for a family member to someday claim them. A few nights ago they had 17 deaths in a shift. The entire unit is only 17 beds.

These patients are so fragile. It’s such a delicate balance of breathing, of blood pressure, of organ function. The slightest movement or change sends them into hours long death spirals. The codes are so frequent those not directly involved barely even register them. The patients are all the same, every one. Regardless of age, health status, wealth, family, or power the diagnosis is the same, the disease process is the same, and the aloneness is the same. Our floor has one guy that made it to extubation. He’s 30 years old. I view him as our mascot, our ray of hope that not everyone here is just waiting to die. I know that most people survive just fine, but that’s not what it feels like in this place. Most of the hospital staff is out sick. We, the disaster staff, keep our n95 masks glued to our faces. We all think we are invincible, but I find myself eyeing up my coworkers, wondering who the weak ones are, knowing deep down that not all of us will make it out of here alive.

A bus takes us back to the hotel the disaster staff resides in, through deserted Manhatten. We are a few blocks from Central Park. We pass radio city music hall, nbc studios, times square. There is no traffic. The sidewalks are empty. My room is on the 12th floor. At 7pm you can hear people cheering and banging on and pans for the healthcare workers at change of shift. This city is breaking and stealing my heart simultaneously. I didn’t know what I was getting into coming here, but it’s turning out to be quite a lot.

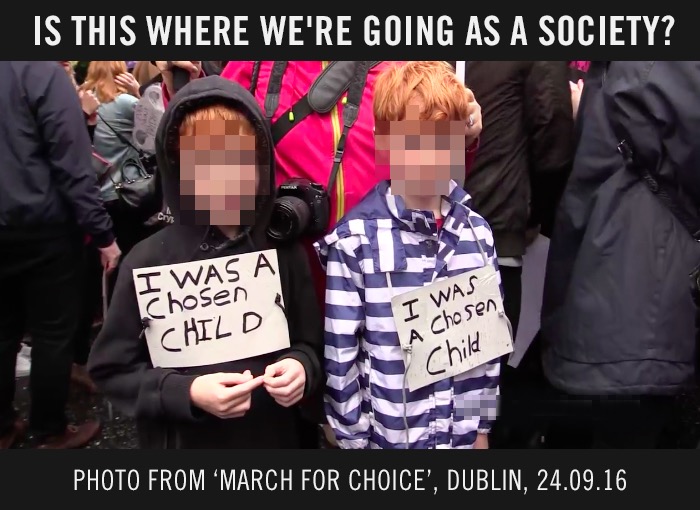

Pawns in a pro-choice game

Pawns in a pro-choice game